The first time I saw The Evil Dead was in 1985. I was 13 or 14 years old and four of my teeth had just been pulled—one of the nastiest experiences of my life. I was lying at home in agony, waiting for the Tylenol-Codeine to do what it was supposed to be doing. I asked my mom to go to the video store (where I worked at the time) to pick up some horror flicks I’d set aside, including one that had just come in—I had no idea what it was about, but the VHS cover showed a young woman in a nightie being dragged into hell by an uprooted, decomposing demon arm: I was in. Mom (bless her) brought the movies back in a flash, I plunged Sam Raimi’s manic, gruesome masterpiece into the VCR, and in less than 10 minutes I had completely forgotten about my teeth. I was smiling instead.

Like Night of the Living Dead, The Evil Dead is one of those inspired cultural moments that change the genre, and filmmaking, forever. A large part of the movie’s magic was conjured by Tom Sullivan, who handled nearly all of the effects for the film, including make-up, animation, and prop building (The Book of the Dead and the ceremonial dagger are his creations). In his 1983 review in The Boston Phoenix, film critic Owen Gleiberman called The Evil Dead “a dreamy delirium of terror” and said of Sullivan’s climactic stop-motion depiction of zombie decay that it was “a special effects coup as stunning as the climactic meltdown in Raiders of the Lost Ark.” It’s so true, and Sullivan did it—not just the one sequence, but all of it—with almost no money and no time.

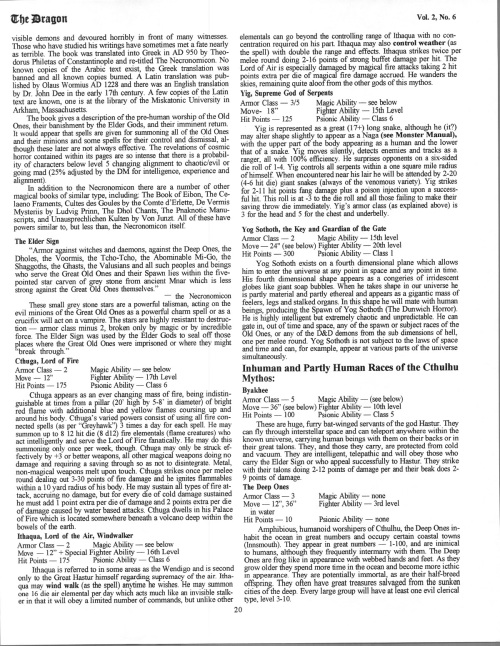

I was really lucky to talk to Tom about The Cry of Cthulhu (“the greatest movie never made”), where he got his start doing pre-production art and sculpting, The Evil Dead, and his tremendous—and overlooked—illustration work on Chaosium’s Call of Cthulhu, one of the smartest and most influential role-playing games of all time.

Tom tours widely and will be appearing next year at Bruce Campbell’s Horror Fest (March 6 – 8) and Cinema Wasteland Movie and Memorabilia Expo (April 10 – 12). Check his website, Dark Age Productions, for a complete, ongoing list of appearances. Anyone interested in purchasing replicas, art prints, or commissions should email Tom at darkageproductions@yahoo.com.

* * *

* * *

2W2N: How did you become involved with The Cry of Cthulhu and what exactly were your responsibilities on the film?

SULLIVAN: I met a magnificent dreamer and one of the to-be producers, Bill Baetz, at the Jackson (Michigan) Space Museum. There was an event that featured J. Allen Hynek of the U.S Government’s Project Bluebook (UFO research organization) fame. Close Encounters of the Third Kind was being released and Professor Hynek was on tour and, being fascinated by UFOs, I had to attend. Bill was working at the Museum and I met him after the presentation. We got to talking about movies and I told him about my artwork. And that set it off. Bill Baetz and David Hurd (a.k.a. Byron Craft) were preparing to make a horror film based on the writings of H.P. Lovecraft. Dave had a script and my job was to illustrate production designs to help promote the film. I was happy to join in. The story was based on the cosmic Lovecraft—not a strange and foul family living outside of town, but portals to terrifying dimensions and journeys to Unknown Kadath. I was new to Lovecraft, so off I went to local used book stores to educate myself on the Cthulhu Mythos.

Bill introduced me to a very young Cary Howe, an ambitious artist full of enthusiasm and talent. We each did sculptures called maquettes of the various creatures the script demanded. We shot them in natural settings and in a few instances used a primitive rear screen projection behind the sculptures. All our work paid off with a great article in Starlog and the late, great Fred Clarke’s Cinefantastique. The articles were written as though the film was being made and that it would be a great venture for potential investors to join in. Alas, it was not to be.

2W2N: Is that why the film didn’t get made, ultimately? Budget difficulties?

SULLIVAN: It didn’t get far enough to have budget difficulties. The story Bill told was that they took the script and articles to Los Angeles to try to sell the film. They pitched it around and finally to a female executive at one of the studios. She said it wasn’t for them and Bill and Dave went home empty handed. Six months later they got a bill from the I.R.S for a half million dollars. It seems that the executive greenlit the project and collected the three million dollar starting fund, leaving a paper trail that made it look like Bill and Dave got the money. I’m guessing she is getting out of prison right about now.

2W2N: How did you come to work for Chaosium on the Call of Cthulhu role-playing game? Was it in part because of the work you did on The Cry of Cthulhu?

SULLIVAN: Back in my married days, my wife Penny and I moved to San Francisco. After months of getting settled in I purchased a table at a comic and film convention in downtown San Francisco and took my artwork to show off. This was in 1982, if I recall. Up comes the late Lynn Willis, who worked for Chaosium on their role-playing games. I had some paintings from my The Cry of Cthulhu production work that sufficiently impressed Lynn to ask me about illustrating for Chaosium. And I said yes.

For the next 18 years I did many game book covers and interior illustrations for them and I kept my copyrights and originals. What I find interesting is that when I am a guest at horror film and comic conventions, Evil Dead fans come up and see my art print gallery filled with Evil Dead and Lovecraft artwork (mostly from Chaosium projects), and they put Evil Dead Tom with Chaosium Tom. And I am thrilled with that.

2W2N: I had no idea what Call of Cthulhu was at the time, but I remember ogling the cover of Shadows of Yog-Sothoth in the hobby shop. It’s really a beautiful piece, and such a perfect distillation of Lovecraft. Was Chaosium pretty specific about what they wanted for each project? Did you work with Sandy Petersen?

SULLIVAN: Chaosium, through Lynn Willis, usually would give me a paragraph or so from some Lovecraft writing appropriate to the game illustration they required. I took the illustrations as if they were book illustrations, so this worked out well for me. While I was aware of Sandy Petersen and his important Call of Cthulhu contributions, we didn’t work closely together. We had our picture taken with Lynn Willis for use as human scale images for the size comparison chart in the back of S. Petersen’s Field Guide to Cthulhu Monsters.

2W2N: The Book of the Dead from the original Evil Dead franchise is one of the most famous horror movie props of all time. How long did you have to design and create it for the first film, and was there a particular inspiration for the overall look?

SULLIVAN: It didn’t take too long to assemble. I had made molds of all the cast members but Bruce [Campbell]. He only had bruises, so he didn’t require a mold. I took Hal Delrich’s mold and slushed some liquid latex into it—about six or seven layers, I think. Then I took some corrugated cardboard and folded it into a book cover. I attached the latex face piece to the cardboard with contact cement. For the pages I used store bought parchment—just dyed, thick paper. I made bindings made of folded grocery bag material and glued the pages into the binding. Later, during the shoot in Tennessee, I would stay up late and draw the pages while I talked film with Josh Becker. And Josh knows his film history. The artwork on the pages was influenced by Da Vinci’s notebooks. I didn’t have a copy with me but I had studied them for years and had a good idea of the look I wanted.

2W2N: The design of the Book of the Dead (Necronomicon Ex Mortis in the sequels) changed with each Evil Dead film. Were you responsible for each of those designs?

SULLIVAN: I designed, built and illustrated the Books for Evil Dead 1 and 2. I believe the art director for Army of Darkness sculpted their derivative version. Not my favorite. They used some of my artwork, photoshopped to combine text and my drawing.

2W2N: With the exception of maybe Jurassic Park, I can’t think of one example of CGI that left me with the same feeling of magic, of total participation in the fantasy, that I get when watching, say, Harryhausen’s skeleton sequence in Jason and the Argonauts. What do you think of contemporary effects, and what do they mean for the future of the fantasy, horror, and sci-fi genres?

SULLIVAN: I am thoroughly blown away by today’s special effects. I do several horror and comic conventions every year and this subject comes up a lot. The fans are unanimously in favor of practical effects. They like the real thing actually there, even if the seams or strings can be seen. As a geek with a passion for and background in stop-motion animation and practical effects, I am actually enthusiastically for CGI effects. When I see Jackson’s King Kong, I see a living, thinking animal actually there. When done with talented animators and artists, properly budgeted and with enough time, what is produced today by CGI techniques is photo-realistic and miraculous. There is still room for the approaches of Harryhausen, O’Brien and the countless other pioneers of cinema magic, as well as other powerful tools to amaze the world.

2W2N: There’s a 2014 documentary about you and your work called Invaluable: The True Story of an Epic Artist. Can you tell me how it came about? Does it span your entire career?

SULLIVAN: I met gung ho filmmaker Ryan Meade over ten years ago and he’s a huge Evil Dead fanatic. Ryan’s been making very entertaining comedies and action films on no budget and they work quite well. He had done an interview with me around 2005 and I think that started the gears turning for him. Once he had made up his mind, we started contacting the Evil Dead gang, cast and crew members, and we started the interview process. And my good friends from Evil Dead came through like the champs they are. I supplied Ryan with my artwork, Super 8mm movies, videotapes, behind the scenes stuff and other materials that fill up the ultimate wish for Evil Dead fans. There is a lot of talk about the Evil Dead film productions, behind the scenes stories and a lot of the unsung heroes of the films. And we are getting great feedback and reviews for Invaluable. I couldn’t be more pleased.

* * *

* * *

___________________________________

For more on Tom’s Evil Dead work, see comprehensive interviews at Book of the Dead and The Digital Bits. There’s also a good video discussion and interview at alt.news 26:46.

Go here to see the trailer for—and buy a copy of—Invaluable: The True Story of an Epic Artist.