The prodigy is toleranceburke.

Archive for the 'Kid Art' Category

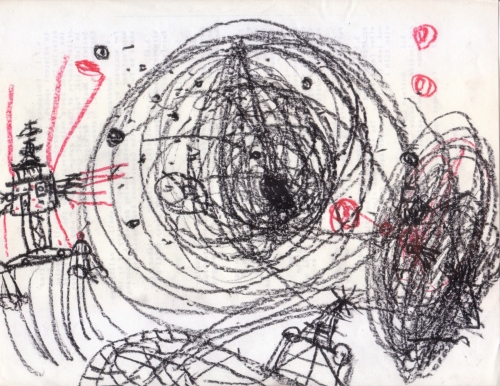

Kid Art: Star Wars (1977)

Published April 21, 2016 Kid Art , Star Wars (Original Trilogy) 3 CommentsKid Art (Circa 1980 – 1985): Dungeons & Dragons

Published April 27, 2015 D&D , D&D Art , Kid Art 3 CommentsI’m going to go ahead and call these drawings masterpieces on par with the Orvis’s illustrations of Disney’s The Black Hole. They’re from Stefan’s Flickr, and there are 91 glorious pieces, all of them perfectly captioned, in his D&D Pencil Art album.

Note the soda machine that has fallen through a “dimensional rift” into D&D world, as well as the bank robbery (“we were low on GP,” says Stefan). Other art not featured here includes a decapitating ninja, a “giant robot warrior machine” shooting down an X-Wing Fighter, an “Apocalypse Arena,” an arm-wrestling dragon, a Sumo warrior, a wizard on a magic carpet dueling a giant eagle, and a bitch-slapping grizzly bear.

The set belongs in a museum.

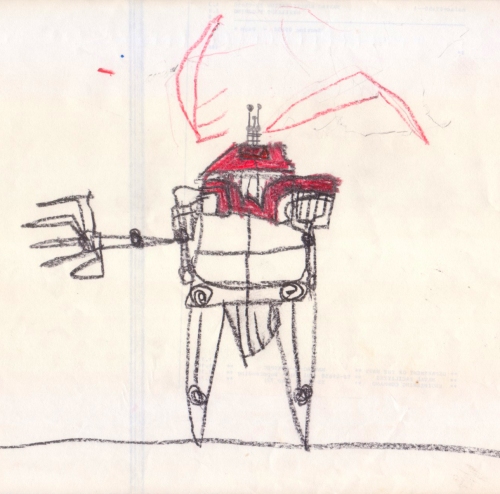

Kid Art (1981): Dungeons & Dragons ‘Knight’

Published April 27, 2015 D&D Art , Fantasy Art , Kid Art 2 CommentsBeautiful D&D-inspired piece artist Joe Linton did when he was in high school. Saved by mom, naturally. I found it on his blog, Homemade Ransom Notes.

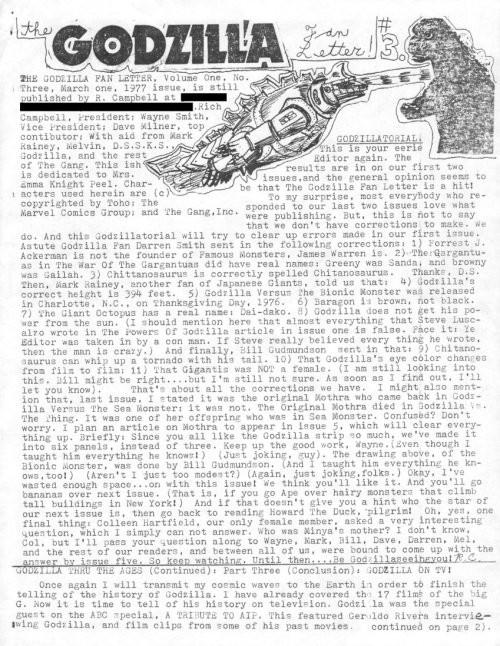

Godzilla Fan Club Newsletters, 1977

Published April 2, 2014 DIY , Fan Clubs , Godzilla , Kid Art 13 CommentsIn Famous Monsters of Filmland #132 (March, 1977), an advertisement appeared for a Godzilla Fan Club. The ad was placed by a gentleman named Richard Campbell.

Nathan Fox, a young Godzilla nut who saw the ad and immediately subscribed, saved all five newsletters (called “fan letters”) produced by Campbell and his team. The detail I left out is that Campbell was 17 or 18 at the time he placed the ad and produced, by hand, the fan letters, all of which have been scanned by Fox in various formats. Read the amazing story and see the letters at Fox’s site.

Could this have been the first American Godzilla fan club? It’s unlikely, but if there had been others in plain sight, I doubt Campbell would have placed his ad (you can see that on Fox’s site as well).

As I’ve said many times before, we were a generation of fans when being a fan meant more than compulsively advertising the fact to the world. It meant building working monuments and monographs to our sources of inspiration.

UPDATE: Japanese film and pop culture scholar August Ragone (Eiji Tsuburaya: Master of Monsters: Defending the Earth with Ultraman, Godzilla, and Friends in the Golden Age of Japanese Science Fiction Film) weighs in on Godzilla fan clubs in the U.S.:

Yep, I had one. The “Godzilla Fan Club” was promoted on both “Creature Features” and “Captain Cosmic” on KTVU-2, since I was serving as their teenaged “Godzilla/Japanese Film Expert.” The beloved host, Bob Wilkins, set it up for me and we ran with it…

The first kit was printed in blue and included a fan club member’s certificate (with artwork by Dennis Lancaster), a newsletter with a cut-out membership card, and a photo of Godzilla. The second wave included a new certificate (with all new artwork by Lancaster), a new newsletter and new cut-out membership card, and a new photo of Godzilla…

And I do recall seeing another “Godzilla Fan Club” in an earlier issue of “Famous Monsters” — possibly in the early-to-mid 1970s (perhaps between 1974-1976). There may also have been one or two advertised in the Want Ad section of “The Monster Times.”

Thanks again, August!

This Book of Homemade D&D Modules Is Better Than Anything Anyone Has Ever Built on Minecraft

Published March 13, 2014 Books , D&D , D&D Modules , DIY , Kid Art 17 CommentsLast year, when I featured Mikey Walters’ homemade D&D modules from 1981, I wondered how many similar old school epics were out there, buried in family attics and basements, one or two small-scale campaigns away from rediscovery. Was there a responsible way to solicit these now historic documents? More important, was there a responsible way to preserve them? The answer is yes, to both questions. The Play Generated Map & Document Archive (PlaGMaDA for short), founded and managed by Tim Hutchings, “collects, preserves and interprets documents related to game play – especially tabletop role playing games and computer games.” People like you and me donate our “play generated cultural artifacts,” and they’re stored in the archives—PlaGMaDA is partnered with The Strong Museum—for all time.

Gaius Stern’s Habitation of the Stone Giant Lord, written and illustrated by the 14-year-old author in 1982, was one such donation. Hutchings decided to combine “Dungeon Module G2²” with seven other D&D-styled adventures, including two of Walters’ modules, and publish them in a book (funded by a successful Kickstarter campaign): The Habitation of the Stone Giant Lord and Other Adventures from Our Shared Youth (2013).

If you’re even a little bit intrigued by the early days of tabletop role-playing and/or the emergent “kid culture” of the time, you will find yourself spellbound by the more than 100 pages inside. (Seriously, someone will need to hit you with a Dispel Magic; otherwise you’ll forget to go to work and feed the kids.) The dedication and detail on display in each of the (playable!) modules is uniquely impressive, and more than that, the authors had no other motive than the challenge, the joy of play, and the promise of sharing their work with fellow adventurers. Some of the writing is damn convincing, too. Here’s a selection from The Lair of Turgon, by Todd Nilson:

The doors, both into and out of this room, are jet black with silver runes upon them. The runes are non-magical: they are an ancient form of cuneiform which relate the eulogy given at Turgon’s burial. A seal of gold had welded the doors shut, but they have evidently been broken by some incredibly powerful force. The hall itself is of granite construction; depicted in bas-relief are scenes from Turgon’s life, from early childhood until his death. This hallway is inhabited by six shadows: more servants of Madros.

The late ’70s and early ’80s saw an explosion of creative energy from young people, who were so deeply inspired by the many novelties and innovations surrounding them that they designed and stitched elaborate costumes from scratch after sketching the real deal inside darkened movie theaters, shot their own Super 8 movies (all of which are better than J.J. Abrams’ Super 8), wrote and drew their own graphic novels, programmed their own (playable!) video games, and, as we see here, wrote, drew, and likely DMed their own fantasy role-playing adventures.

Jon Peterson, the author of what many consider to be the definitive history of wargames and role-playing games, Playing at the World, wrote the excellent introduction to Habitation. Before breaking down each of the featured home-brewed adventures, noting (compellingly) where the creators borrowed from the Monster Manual or the Fiend Folio, what D&D edition was used as a foundation, and so on, Peterson takes us on a comprehensive tour through the early years of TSR, from the company’s beginning promise of making us “authors and architects” of our own fantasies, to the introduction of the adventure module format that Peterson finds somewhat antithetical to that original promise. “When we purchase and rely on a module,” he writes, “are we letting TSR do our imagining for us?”

It’s a fair question, and he says of the works in Habitation that

Each of them, in its own way, illustrates the tension between the commercialization of adventure scenarios and the original invitation of D&D to invent and collaborate and share.

And later:

Players were not content to have TSR do their imagining for them, and when the production of pre-packaged modules began, players responded by positioning themselves as creators of modules and thus as peers of TSR, rather than mere consumers.

Ultimately, I don’t agree with his conclusion. First, I don’t think any of the young authors featured in Habitation were “positioning” themselves to be anything; the modules look to me like a labor of love and, if anything, an homage to and emulation of TSR, as Peterson himself mentions elsewhere. Second, the module format was a signal innovation that expanded the role-playing genre and broadened the player base. Gamers young and old continue to run, tweak, perfect, and be inspired by the likes of The Keep on the Borderlands and Dark Tower. Third, as I’ve argued elsewhere, all D&D products—be it the original set of 1974 or the Dragonlance franchise—are commercial products. TSR certainly did reach a point—in 1982/1983, in my opinion—at which building and inflating the D&D brand took precedence over crafting quality “products of your imagination.” I believe this is Peterson’s larger point, and it’s well taken.

A page from The Tomb of the Areopagus the Cloaked and Japheth of the Mighty Staff, by Michael M. Hughes

What makes the work collected in Habitation so historic, and Peterson talks about this as well, is that it captures how real players approached D&D at a time when “playing mind games with dice,” to use Chris Hart’s phrase, was so profoundly untried. The game gave young people such an unprecedented amount of imaginative freedom, in fact, that it became a malignant bogeyman to those who rejected the idea that young people deserved any freedom, and who were terrified of dreamers and freethinkers of all ages.

In short, please consider getting yourself a copy of Habitation right here, and have a look through PlaGMaDA’s incredible archive right over here. And after that, maybe you’ll delve into those musty trunks and dot matrix computer paper boxes and dig out your old character sheets, your #2 pencil-drawn grid paper dungeons that not even a Conan-Gandalf multiclass could survive, your lengthy and grammatically suspect descriptions of demilich lairs and warring sky-castle kingdoms. Hell, PlaGMaDA will take a scrap of paper with nothing but your scribbled (and probably padded, let’s be honest) ability score rolls. Donate it all right here. You don’t even have to use your real name, although you really should, because what you made with your own mind and hands from scratch and for the love of the game when you were 12 years old is better than whatever Wizards of the Coast is putting out next, and more awesome than anything anyone has ever built on Second Life or Minecraft.

‘Visions of Lunar Life’: 2009 NASA Art Contest Winners

Published September 26, 2013 Kid Art , Sci-Fi/Space Art , Space Travel/Exploration Leave a CommentDamn good stuff from the high school division—better than the university division, in my opinion. See all the winners here. The Nasa Art Contest was discontinued in 2012 due to—guess what?—lack of funding.

Kid Art (1982): Raiders of the Lost Ark

Published July 19, 2013 Kid Art , Raiders of the Lost Ark 3 CommentsNeil Whelan describes his fine work:

On 12 June 1981, Raiders Of The Lost Ark was released in America. Alongside Star Wars, it was a defining film for a generation and 30 years later it’s still one of my top three favourite films of all time.

As was the tradition back in those days before DVD and high definition, films stayed at the cinema for months [after] their initial release rather than being pulled from screens after a couple of weeks.

By the look of this old text book, I didn’t get to see it until 17 April 1982, eventually reviewing it the following Thursday. I think I summed up the plot pretty well and you can instantly see what my favourite scene was.

You have to admit, it is a damn good plot summary, and he nails the scene.

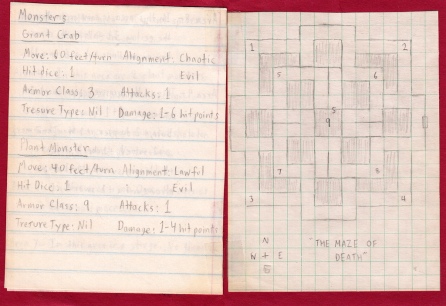

Homemade D&D Modules: The Golden Scepter of the Troll Fens, The Maze of Death, and The Priest of Evil (1981)

Published April 24, 2013 D&D , D&D Modules , DIY , Kid Art 9 Comments

Hand-drawn, hand-typed, and hand-assembled by 13-year-old Mikey Walters in 1981, I present the first six pages of a fully realized, fully playable 28-page module. (Click the images for a bigger view.)

Your mission, if you choose to accept it, is to journey to the Troll Fens, retrieve the golden scepter (it “can cause Orcs to do any task, including suicide”), and bring it safely back to the Kingdom of Kala. The scepter is gold and exactly 5 ft. long, as you can see. If you find a golden scepter measuring 4 ft. or 6 ft., that’s totally cool, but it’s not the golden scepter we’re looking for.

How far is the Troll Fens from Kala, you ask? Well, it’s 575 miles by the main road, or “250 miles as the bird flies.” Those birds have all the luck! If you happen to doubt the accuracy of the distances, you have but to consult the awesomely rendered map. (I thought it was very biblical/philosophical of Mikey to put the Island of Evil and the Island of Knowledge side by side.)

Wait, there’s more.

I really could have used these “Mini Modules” back in the day, since only two of us were serious about playing (serious about wanting to play, anyway). The covers are made of construction paper. The “Basic” banner on top is pure genius.

The cover of The Priest of Evil is pretty creepy, isn’t it? What’s he doing in that chair? Is he commanding the fire? Why won’t he show himself? Oh my God he’s going to kill us all with his mind!

Okay, one more page. I can’t resist. This one is from Mikey’s new monsters stat pages.

“A Mad Dog is simply a dog with Rabies.” And let me tell you, the Rabies is nasty. “Within four days the victim will have great difficulty swallowing water… and in twelve days they will die.” A constitution or strength of 18 or better will give you a mere 10% chance of survival. Note to party: steer clear of Mad Dogs.

“A Jinnis is a disgusting creature that lives in swamps and other dark places.” You know, despite its sandpaper-like texture and devil horns and fire breath, I feel like the Jinnis gets a bad rap. This thing has a mother that loves it. For all we know, the Jinnis thinks we’re disgusting creatures that live in kingdoms and other sickeningly well-lighted places.

You’ll find the entire modules and other gems at Mikey’s D&D Memories Set on Flickr.

Also, the modules appeared last year at Rended Press, where they were kindly made available as PDFs: The Golden Scepter of the Troll Fens, The Maze of Death, The Priest of Evil.

STAY TUNED: Mikey was kind enough to talk to me about his D&D creations and other childhood endeavors and experiences. The interview will run next week.

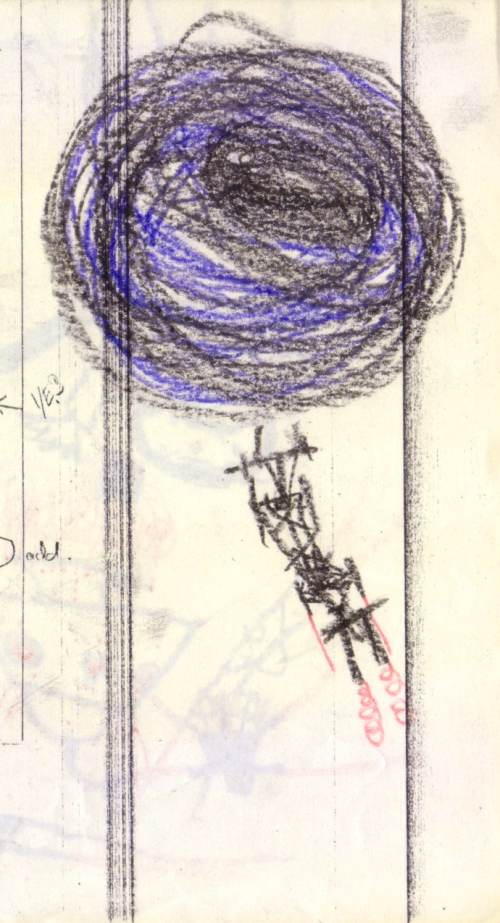

The Story of The Black Hole Told through the Childhood Drawings of Ryan and Ginger Orvis

Published March 15, 2013 Black Hole, The , Kid Art 3 CommentsThis might be the best thing I’ve ever found on the internet. Ryan Orvis, a musician and pop culture hound, presents these treasures from his (and our) youth on his blog, Blanked as Ordered.

Ryan says of the film and the drawings,

Like many kids, my sister and I went to see the film during its opening week. We returned from the theater in tears. I couldn’t process whether I liked the movie or not. All I knew was that I was upset, but couldn’t stop thinking about it. Eventually we stopped crying, and began the cathartic mission of drawing all the memorable scenes from the film.

I recently found, organized and scanned all the Black Hole drawings we made as kids. I’m not sure how many days we worked on them, but they were created on several different types of paper, using a combination of crayons and ink pens. Amazingly, they pretty much explain the plot of the movie, although it comes across as much more violent and action-packed than it really is.

Then, just as I’m getting all sentimental about how we actually did things like this, and why we did things like this, the drawings take on a significance I can’t even describe.

Sadly, my sister Ginger passed away a few years later, so I am unable to get her thoughts on the experience. I also am not 100% sure how many of these drawings were hers. I think the majority were mine, because even at that age I was a pretty big nerd, and it’s the sort of thing I would do.

Ryan has written about the pictures, pithily and hilariously, in three parts. Go read them. And, according to this post, he has saved all of his and Ginger’s drawings from the days when kid culture inspired this kind of passion, dedication, and attention to detail. (The resemblance of some of the depictions above to their corresponding scenes in the film is un-fucking-canny.)

All of the art posted here is, needless to say, © Ryan Orvis.