Last year, when I featured Mikey Walters’ homemade D&D modules from 1981, I wondered how many similar old school epics were out there, buried in family attics and basements, one or two small-scale campaigns away from rediscovery. Was there a responsible way to solicit these now historic documents? More important, was there a responsible way to preserve them? The answer is yes, to both questions. The Play Generated Map & Document Archive (PlaGMaDA for short), founded and managed by Tim Hutchings, “collects, preserves and interprets documents related to game play – especially tabletop role playing games and computer games.” People like you and me donate our “play generated cultural artifacts,” and they’re stored in the archives—PlaGMaDA is partnered with The Strong Museum—for all time.

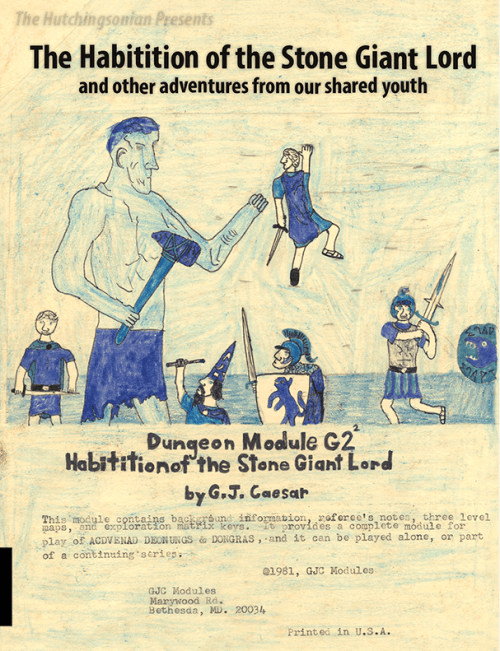

Gaius Stern’s Habitation of the Stone Giant Lord, written and illustrated by the 14-year-old author in 1982, was one such donation. Hutchings decided to combine “Dungeon Module G2²” with seven other D&D-styled adventures, including two of Walters’ modules, and publish them in a book (funded by a successful Kickstarter campaign): The Habitation of the Stone Giant Lord and Other Adventures from Our Shared Youth (2013).

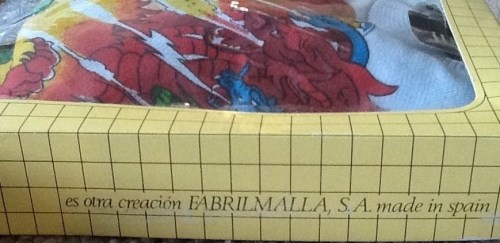

Detail from Habitation of the Stone Giant Lord, by Gaius Stern

If you’re even a little bit intrigued by the early days of tabletop role-playing and/or the emergent “kid culture” of the time, you will find yourself spellbound by the more than 100 pages inside. (Seriously, someone will need to hit you with a Dispel Magic; otherwise you’ll forget to go to work and feed the kids.) The dedication and detail on display in each of the (playable!) modules is uniquely impressive, and more than that, the authors had no other motive than the challenge, the joy of play, and the promise of sharing their work with fellow adventurers. Some of the writing is damn convincing, too. Here’s a selection from The Lair of Turgon, by Todd Nilson:

The doors, both into and out of this room, are jet black with silver runes upon them. The runes are non-magical: they are an ancient form of cuneiform which relate the eulogy given at Turgon’s burial. A seal of gold had welded the doors shut, but they have evidently been broken by some incredibly powerful force. The hall itself is of granite construction; depicted in bas-relief are scenes from Turgon’s life, from early childhood until his death. This hallway is inhabited by six shadows: more servants of Madros.

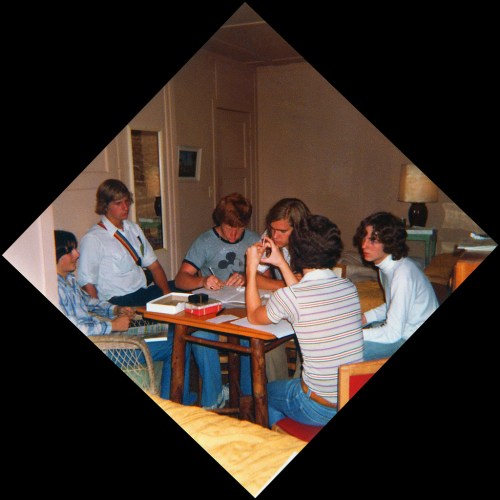

The late ’70s and early ’80s saw an explosion of creative energy from young people, who were so deeply inspired by the many novelties and innovations surrounding them that they designed and stitched elaborate costumes from scratch after sketching the real deal inside darkened movie theaters, shot their own Super 8 movies (all of which are better than J.J. Abrams’ Super 8), wrote and drew their own graphic novels, programmed their own (playable!) video games, and, as we see here, wrote, drew, and likely DMed their own fantasy role-playing adventures.

Stone Castle/Castle Stone from Stone Death, by Richard C. Benson

Jon Peterson, the author of what many consider to be the definitive history of wargames and role-playing games, Playing at the World, wrote the excellent introduction to Habitation. Before breaking down each of the featured home-brewed adventures, noting (compellingly) where the creators borrowed from the Monster Manual or the Fiend Folio, what D&D edition was used as a foundation, and so on, Peterson takes us on a comprehensive tour through the early years of TSR, from the company’s beginning promise of making us “authors and architects” of our own fantasies, to the introduction of the adventure module format that Peterson finds somewhat antithetical to that original promise. “When we purchase and rely on a module,” he writes, “are we letting TSR do our imagining for us?”

It’s a fair question, and he says of the works in Habitation that

Each of them, in its own way, illustrates the tension between the commercialization of adventure scenarios and the original invitation of D&D to invent and collaborate and share.

And later:

Players were not content to have TSR do their imagining for them, and when the production of pre-packaged modules began, players responded by positioning themselves as creators of modules and thus as peers of TSR, rather than mere consumers.

Ultimately, I don’t agree with his conclusion. First, I don’t think any of the young authors featured in Habitation were “positioning” themselves to be anything; the modules look to me like a labor of love and, if anything, an homage to and emulation of TSR, as Peterson himself mentions elsewhere. Second, the module format was a signal innovation that expanded the role-playing genre and broadened the player base. Gamers young and old continue to run, tweak, perfect, and be inspired by the likes of The Keep on the Borderlands and Dark Tower. Third, as I’ve argued elsewhere, all D&D products—be it the original set of 1974 or the Dragonlance franchise—are commercial products. TSR certainly did reach a point—in 1982/1983, in my opinion—at which building and inflating the D&D brand took precedence over crafting quality “products of your imagination.” I believe this is Peterson’s larger point, and it’s well taken.

A page from The Tomb of the Areopagus the Cloaked and Japheth of the Mighty Staff, by Michael M. Hughes

What makes the work collected in Habitation so historic, and Peterson talks about this as well, is that it captures how real players approached D&D at a time when “playing mind games with dice,” to use Chris Hart’s phrase, was so profoundly untried. The game gave young people such an unprecedented amount of imaginative freedom, in fact, that it became a malignant bogeyman to those who rejected the idea that young people deserved any freedom, and who were terrified of dreamers and freethinkers of all ages.

In short, please consider getting yourself a copy of Habitation right here, and have a look through PlaGMaDA’s incredible archive right over here. And after that, maybe you’ll delve into those musty trunks and dot matrix computer paper boxes and dig out your old character sheets, your #2 pencil-drawn grid paper dungeons that not even a Conan-Gandalf multiclass could survive, your lengthy and grammatically suspect descriptions of demilich lairs and warring sky-castle kingdoms. Hell, PlaGMaDA will take a scrap of paper with nothing but your scribbled (and probably padded, let’s be honest) ability score rolls. Donate it all right here. You don’t even have to use your real name, although you really should, because what you made with your own mind and hands from scratch and for the love of the game when you were 12 years old is better than whatever Wizards of the Coast is putting out next, and more awesome than anything anyone has ever built on Second Life or Minecraft.