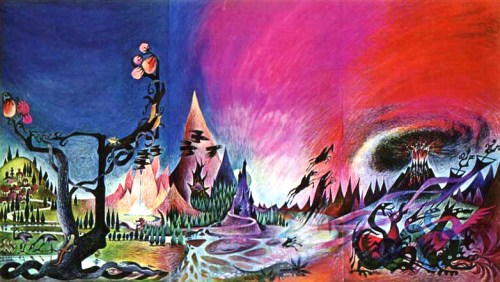

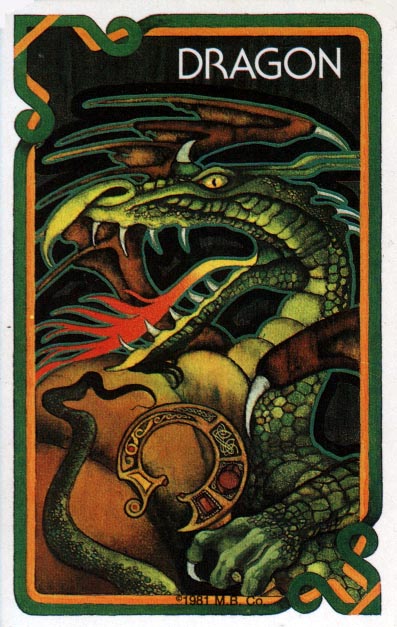

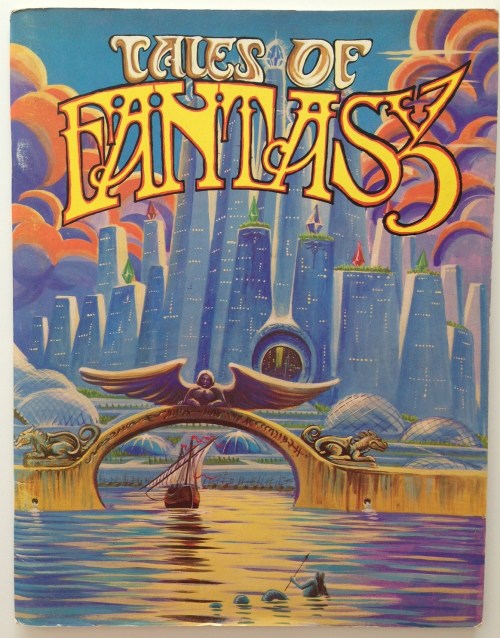

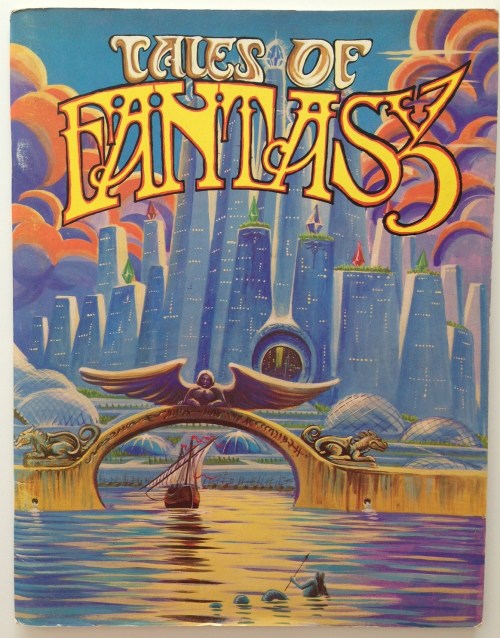

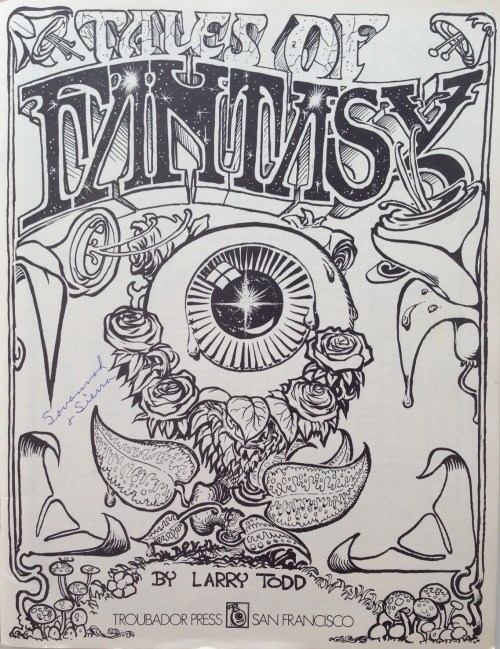

I’ve briefly talked about Tales of Fantasy before. It’s one of the formative books of my youth, and I was very fortunate to find a copy in good condition. I asked Malcolm Whyte, founder and longtime director of Troubador Press, whose idea it was and how the project came together, and here’s what he said:

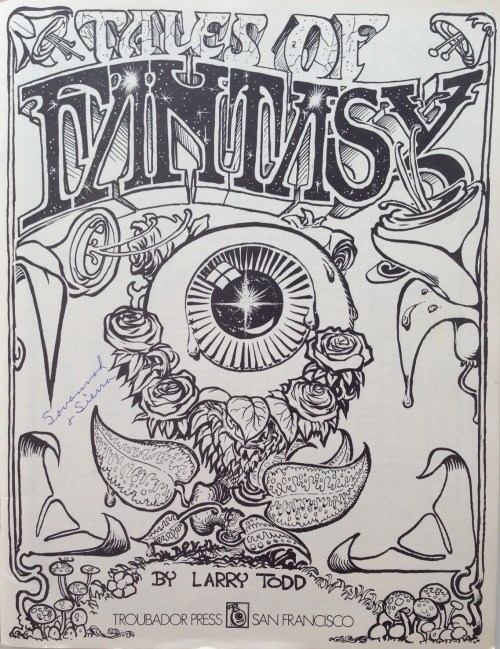

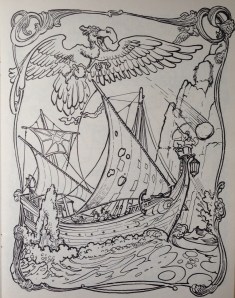

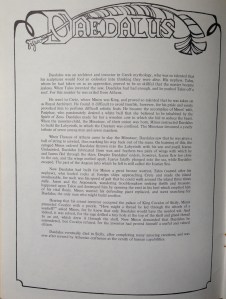

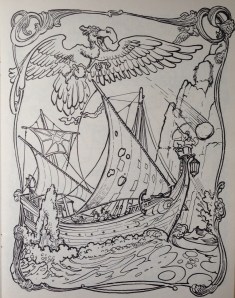

Tales of Fantasy was my idea. I wanted to round out a trilogy—a fantasy trilogy—that started with Monster Gallery (1973) and included Science Fiction Anthology (1974). All three books were then marketed as a set: if someone had one of the books, he must have the other two. I was also interested in having some of the underground cartoonists illustrate Troubador books. I knew of Larry Todd’s interest in science fiction from the underground comix he wrote for and especially his wonderful Dr. Atomic character, and signed him up for Tales of Fantasy.

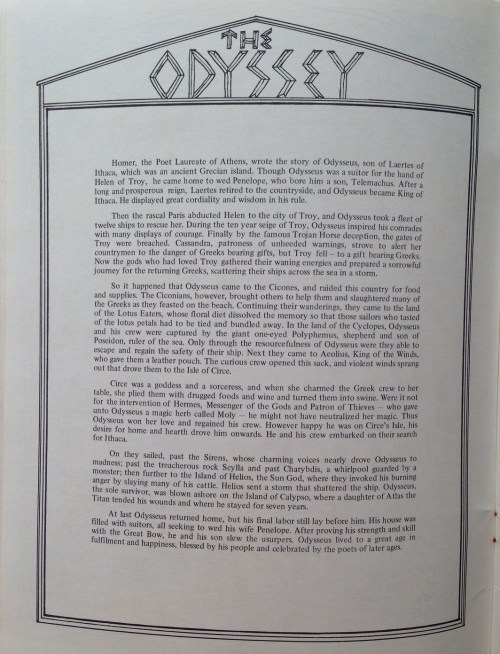

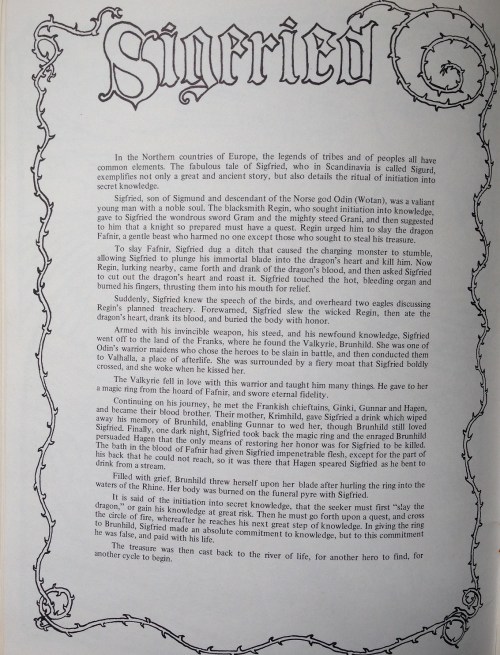

As we were discussing which tales to include in the book, I was astounded by Larry’s depth of knowledge of great fantasy authors and realized that he had to write the book as well as illustrate it. Tales of Fantasy has more text than most of the other Troubador coloring albums.

Larry is a sweet, engaging, literate, post-hippy eccentric… Last I knew he was one of the few of a dying breed of hand-done sign painters.

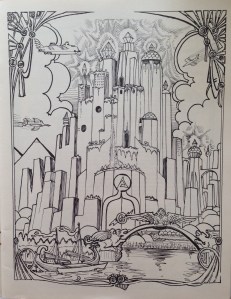

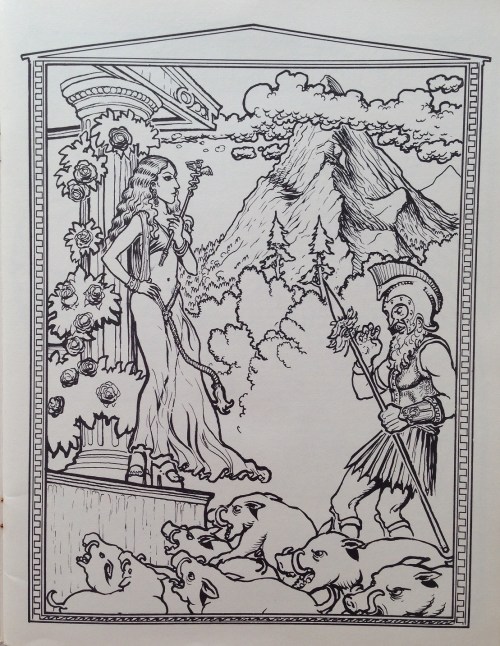

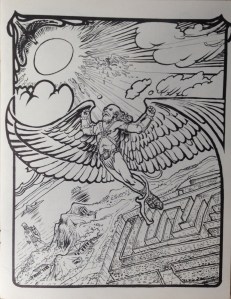

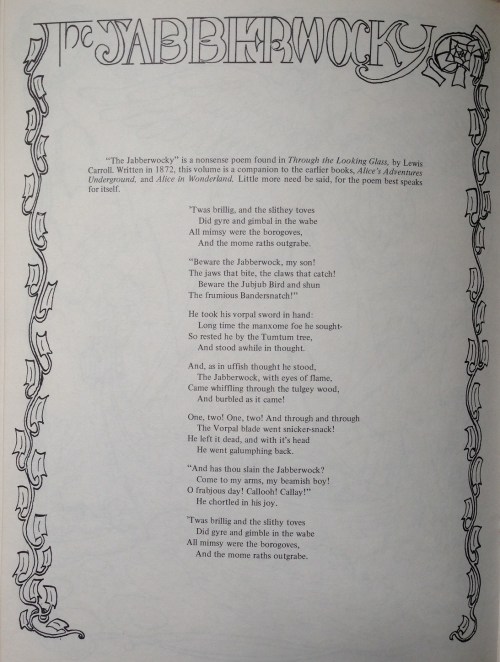

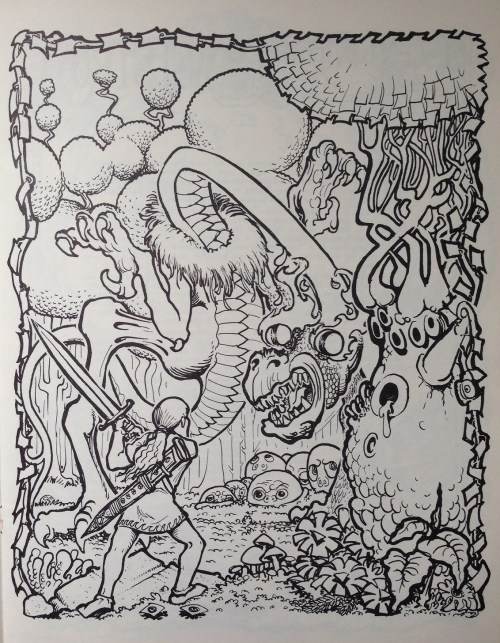

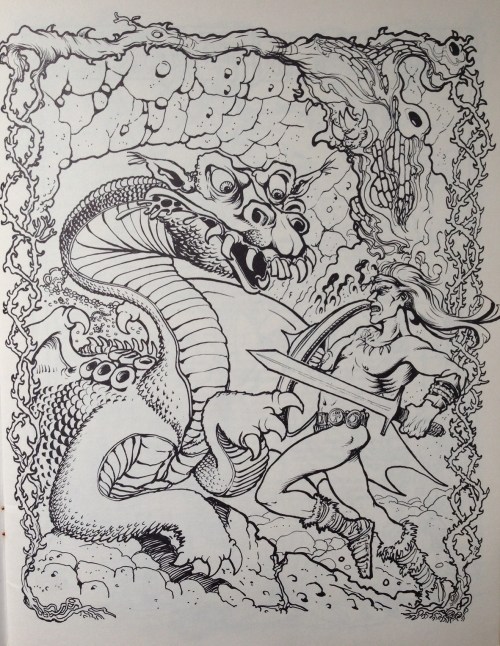

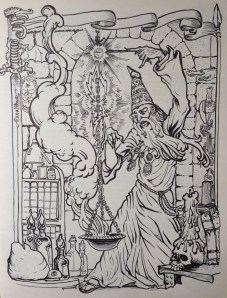

Troubador’s `fantasy trilogy’ marks a high point not only in coloring books (fine art coloring albums, actually), but in the kind of intelligent entertainment publishers and culture creators once offered young people. Todd’s descriptions of the various tales are exciting and comprehensive, and his art is as enthralling today as it was then.

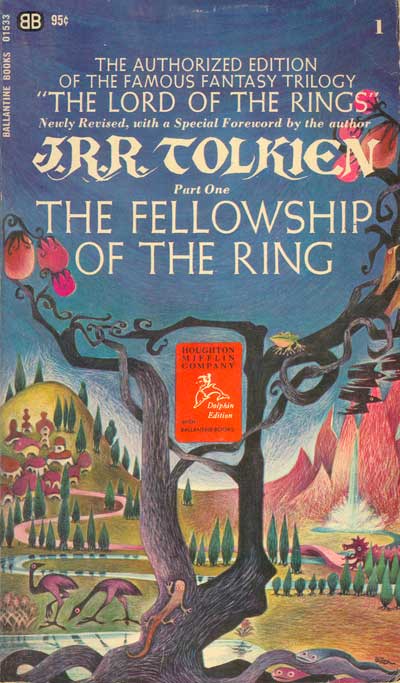

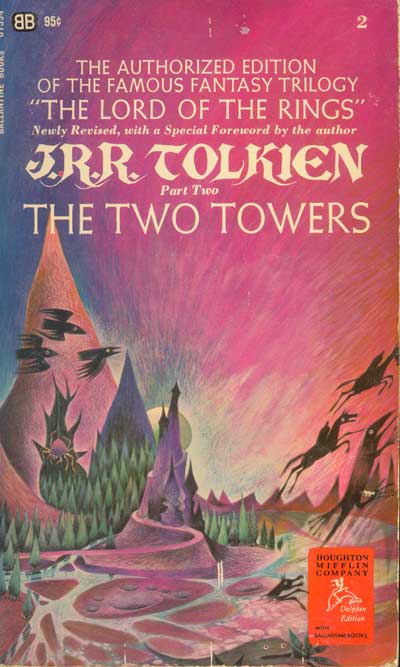

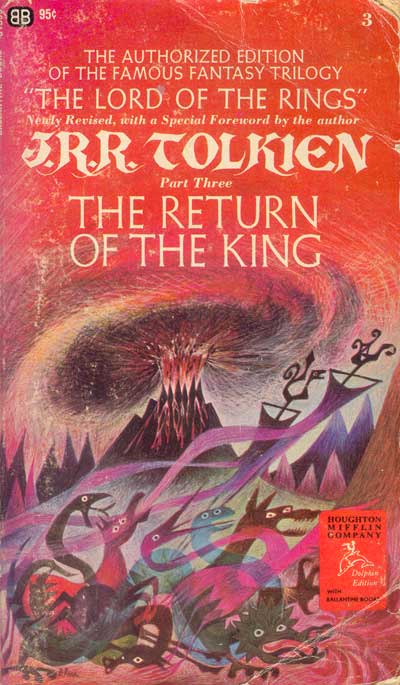

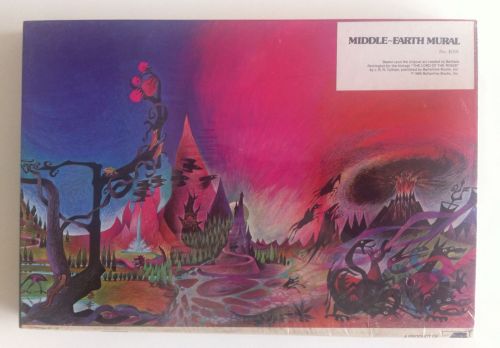

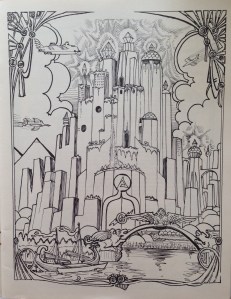

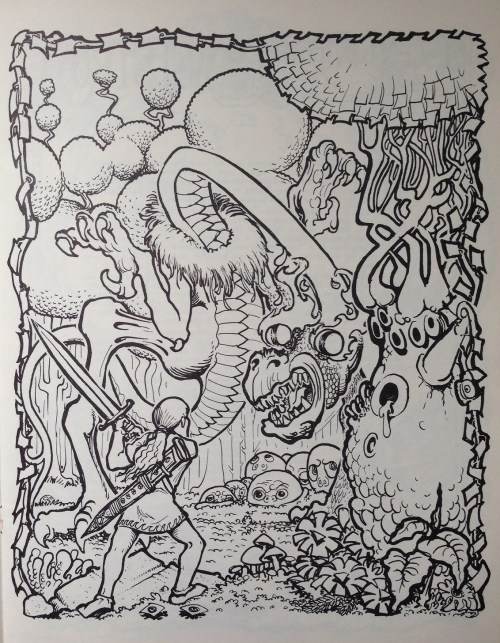

Fantasy became a genre proper when the young people of the 1960s embraced and popularized The Lord of the Rings. In fact, there’s an important passage about Tolkien’s influence in Theodore Roszak’s definitive analysis of the `youth opposition’, The Making of a Counter Culture (1969):

The hippy, real or as imagined, now seems to stand as one of the few images toward which the very young can grow without having to give up the childish sense of enchantment and playfulness, perhaps because the hippy keeps one foot in his childhood. Hippies who may be pushing thirty wear buttons that read “Frodo Lives” and decorate their pads with maps of Middle Earth (which happens to be the name of one of London’s current rock clubs). Is it any wonder that the best and brightest youngsters at Berkeley High School… are already coming to class barefoot, with flowers in their hair, and ringing with cowbells?

The allure of fantasy literature was (and still is, to many) that it offers a vision of “the days when the world was uncrowded and unregulated and ‘natural’ man flourished.” Emulating Middle Earth and its intrepid adventurers—even channeling the Cthulhu mythos of H.P. Lovecraft—was a form of protest against the crass industrial establishment, which Roczak called the ‘technocracy’.

Most of the territory geeks claim today was inherited from literate post-hippies like Larry Todd, thanks in part to literate, daring publishers like Malcolm Whyte.