I really enjoyed Ethan Gilsdorf’s homage to D&D over at Boing Boing. The game, now 40 years old, clearly changed his life for the better, and his affection for it is absolutely genuine. However, I was a little surprised when I got to this passage:

Like a 3rd level Spell of Suggestion, D&D generated subtle repercussions through the culture. The role-playing game opened new pathways for creativity, new ways for kids and young adults to entertain themselves. The game led a DIY, subversive, anti-corporate revolution, a slow-building insurrectionist attack against the status quo of leisure time and entertainment.

While D&D certainly did promote the DIY aesthetic and overturn the gaming status quo, it certainly did not lead any anti-corporate revolution. TSR was a corporation, and it became quite a powerful one. Its core products—rulebooks, modules, miniatures, various supplements—were damn expensive from the beginning, so much so that the game was out of reach for lots of kids who wanted to try it. There’s a reason treasure is so important in D&D, in some cases equaling experience points: art imitates life.

True, once players understood the essential ingredients of D&D, they could home brew their own modules and adventures, but it wasn’t a political act (there was no role-playing “movement”), and most everyone was using “corporate” props, from TSR or one of its legion of imitators. We thought D&D was cool. We were emulating, not disassociating.

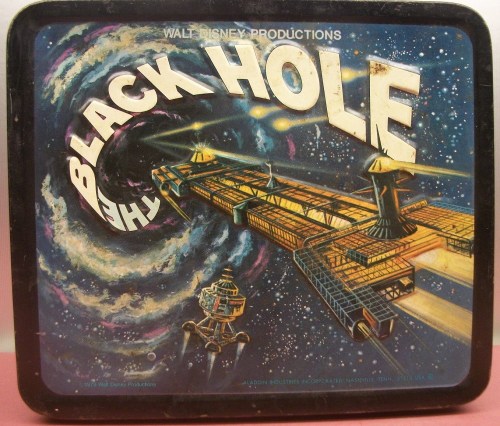

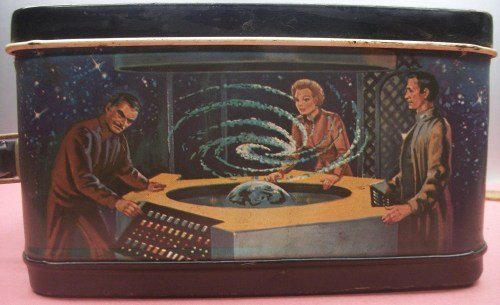

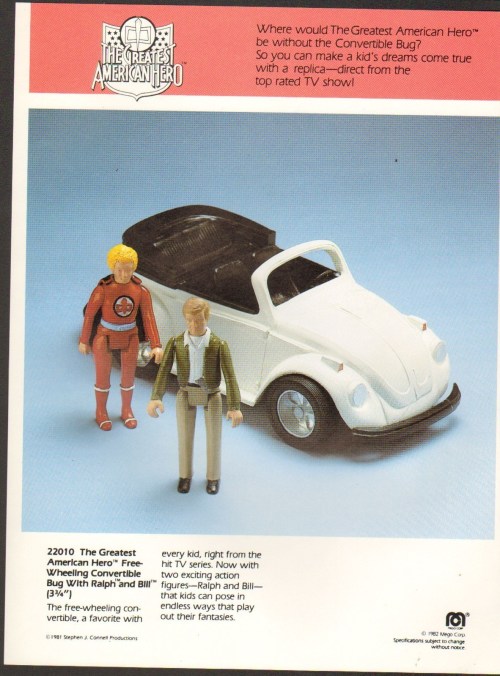

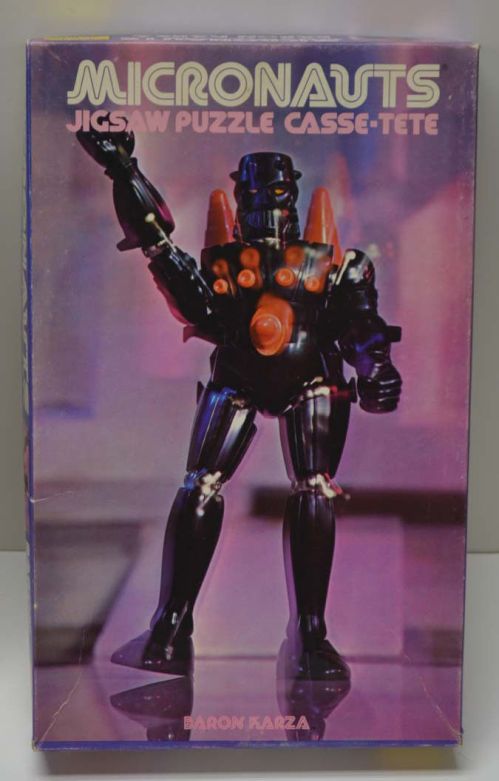

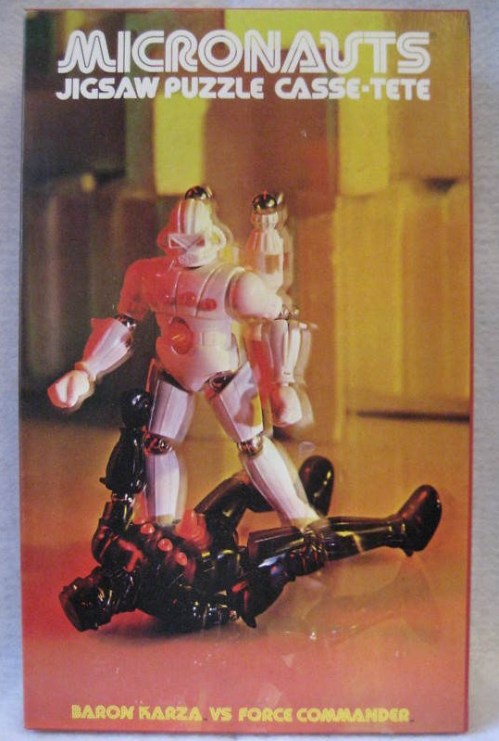

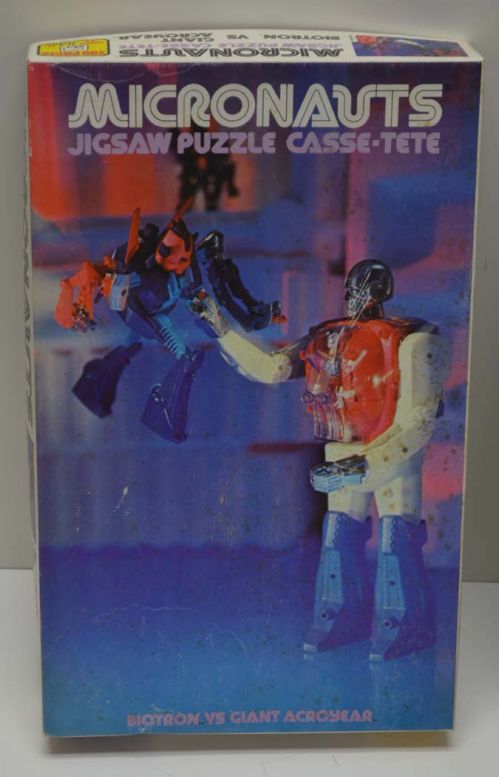

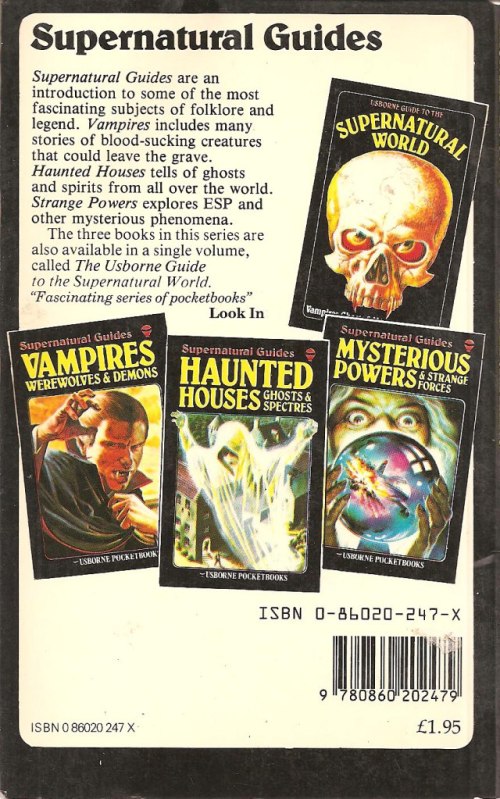

By 1983, it was clear even to my 11-year-old self that TSR had “gone mainstream”: out came the action figures, the animated series, the profligate licensing, kid’s storybooks, pencil sharpeners, beach towels—all of the trappings of a runaway corporate culture looking to replicate itself for as long as possible. In short, the business expanded beyond role-playing: D&D became a brand. You can say what you will about the move. It worked. D&D is still around, still being discovered by successive generations, just like Macintosh and Vans and G.I. Joe.

Here’s Gilsdorf again:

The lesson of Dungeons & Dragons has always been this: make your own entertainment. By sitting around a table, face to face, and arming yourself with pencils, graph paper, and polyhedral dice, you can tap into what shamans, poets and bards have done all the way back to the Stone Age. Namely, the making of a meaningful story where the tellers have an emotional stake in the telling, and the creating of a shared experience out of thin air.

To go on this new adventure, you don’t absorb a movie or TV show passively, on the couch, or merely “read” a book. Nor are your options for “interacting” with a fantasy experience limited to collecting merchandise or playing with action figures. Best of all, the essential quality of this unique, narrative gaming experience can’t be co-opted as commercial entertainment. Role-playing games like D&D are a way to experience unstructured free time while imposing upon it a structure, a story.

I love that first paragraph. He totally captures what made D&D and role-playing so starkly novel and exciting: you’re an individual playing a character you created within a narrative you’re helping to write. I’m not sure what he means by the following, though: “this… narrative gaming experience can’t be co-opted as commercial entertainment.” No gaming experience can be co-opted—unless we’re talking about the Hunger Games. If I play Mouse Trap with my family, Hasbro doesn’t own our experience. If I play poker with my friends, Hoyle doesn’t somehow contaminate the proceedings. My point is that traditional games are just as meaningful to the people who play and enjoy them. Not everyone has the time required, or the players required, for a Greyhawk campaign.

I think it’s important not to overstate the importance of D&D and role-playing, especially with fewer and fewer young people picking up books, the bedrock of literature, philosophy, history, and a few other notable human endeavors. Nothing works the imagination like serious reading, with the exception of writing. The “passivity” of reading is a myth advanced by technophiles who make or stand to make fortunes on “interactive” digital technologies. “D&D beats digital hands down,” Gilsdorf writes in his essay. Damn straight. Reading beats both.

The truth is that D&D and fantasy role-playing games gave kids disenchanted with the tedious real world (i.e. the adult world) instructions on how to build new ones, unlimited by time or place or possibility. Once we were able to decipher those instructions, we became explorers of the mind. That’s the most we can or should expect from any game.

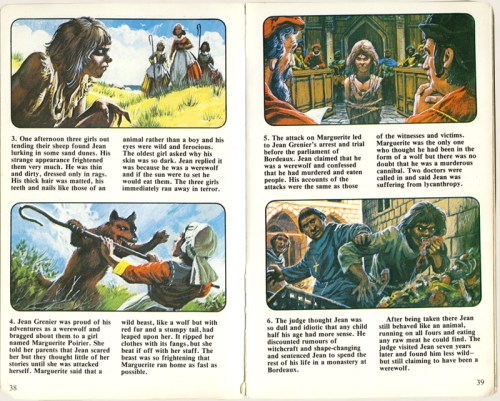

(Image via Hack & Slash)