Archive for January, 2016

Richard Corben Cover Art: Anomaly #3 (1971)

Published January 22, 2016 Comic Books , Richard Corben , Underground Comix Leave a CommentNeal Adams Concept Art for Unmade Childhood’s End Mini-Series, Circa 1980

Published January 21, 2016 Magazines/Zines , Starlog 6 CommentsLong story short: The project met with Arthur C. Clarke’s approval, but producer Phil DeGeure could not get Universal to put up the huge budget needed to start production. DeGeure was a fan of Adams, who did not disappoint with his conceptual designs.

The article is from Starlog #42 (January, 1981).

Hat tip Martin Kennedy.

Here’s the X-ploratrons backstory, and below is the ad from the 1979 Corgi catalog. The first ad is illustrated by British artist Frank Langford.

(Images via combomphotos/Flickr and Moonbase Central)

Corgi’s The X-ploratrons (1979)

Published January 20, 2016 2000 AD , Adventure 2000 , Corgi Toys , X-ploratrons 5 CommentsThe X-ploratrons were Corgi’s short-lived (and ill-named) answer to Matchbox’s Adventure 2000 line. They seem to have been produced for one year only, and there were four vehicles in total, each featuring specialized equipment: Lasertron (reflector), Magnetron (magnet), Rocketron (firing rocket, working compass), and Scanotron (magnifying lens).

The X-ploratrons, according to the backstory, were created to combat a nature that’s gone wild in a 21st century post-apocalyptic world. While the the actual product doesn’t match the quality and imagination of the Adventure 2000 line, the art is superior: all of the package illustrations were done by Carlos Ezquerra, a longtime 2000 AD alum and the co-creator of Judge Dredd and Strontium Dog. Interestingly, Adventure 2000’s Raider Command vehicle appears in a 1978 Judge Dredd story arc called The Cursed Earth.

More views below, and more on the X-ploratrons later.

(Images via The Saleroom, Vectis Auctions, and The Toy Cabin)

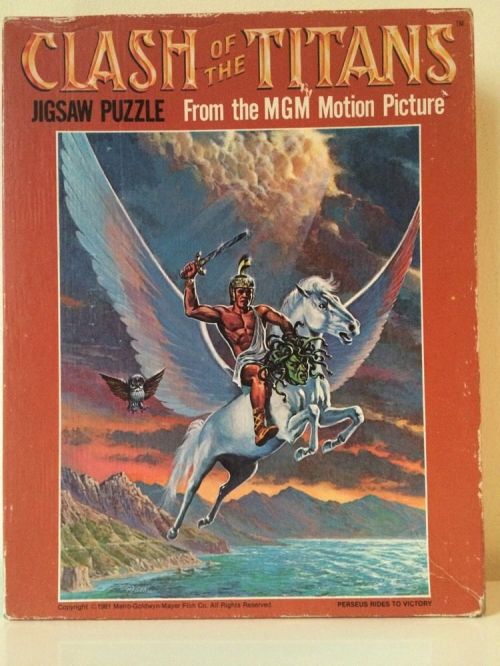

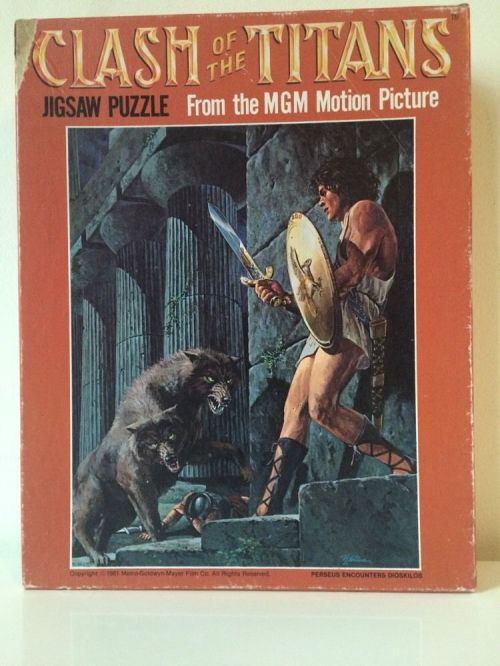

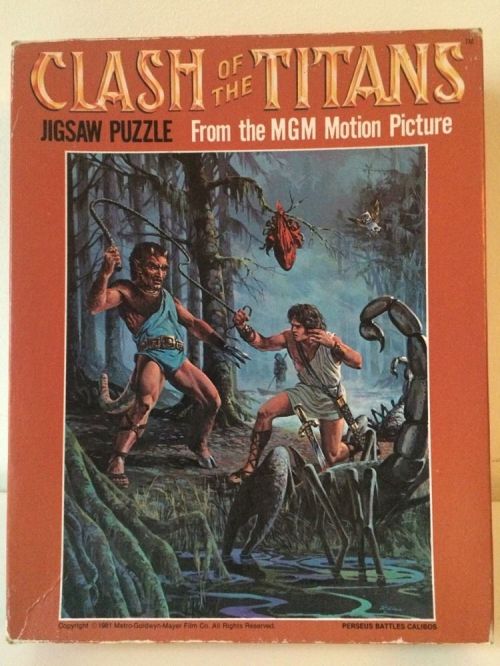

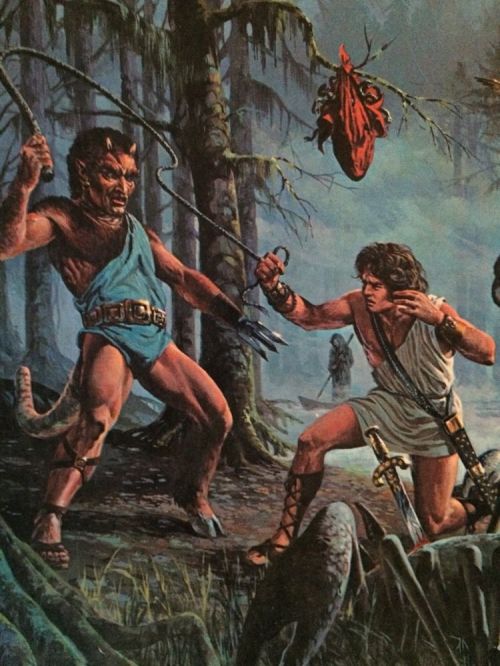

Clash of the Titans Jigsaw Puzzles (Whitman, 1981)

Published January 19, 2016 Clash of the Titans , Jigsaw Puzzles 11 CommentsHere are three of the four puzzles produced by Whitman. You can see them all in the last shot. The same artist painted all of the covers, but I can’t make out the signature.

UPDATE (1/21/16): Thanks to Ian for identifying the artist as R.L. Allen. Allen did a series of Universal Monster jigsaw puzzles for Whitman in the late 1960s, as well as quite a bit of work for the Masters of the Universe franchise.

Clash of the Titans Illustrated Storybook (Golden Press, 1981)

Published January 19, 2016 Books , Clash of the Titans Leave a CommentThe First Sword and Sorcery Movie Was Almost Thongor: In the Valley of the Demons

Published January 14, 2016 Magazines/Zines , Starlog 5 CommentsAmicus Production’s Milton Subotsky gave us some of the most beloved B films of the 1960s and 1970s, including two of my all-time favorites: The Land That Time Forgot (1974) and The People That Time Forgot (1977). Too bad we were denied his sword and sorcery extravaganza that would have featured stop-motion animated “air boats,” “lizard-hawks,” “giant flying spiders,” and a “Dragon-God,” not to mention David “Darth Vader” Prowse in the role of the barbarian hero. Subotsky wanted to do a Conan movie very early on, possible as early as the late 1960s, but he couldn’t get the rights. He settled for Lin Carter’s copycat, Thongor.

The article, from Starlog #15 (August, 1978), has Thongor: In the Valley of the Demons slated for a July 1979 release, but it was not to be. Both Clash of the Titans and Conan the Barbarian were in development, and Subotsky couldn’t get the money he needed to compete with the talent involved (namely, Ray Harryhausen).

The first live action sword and sorcery movie was, instead, 1980’s Hawk the Slayer.

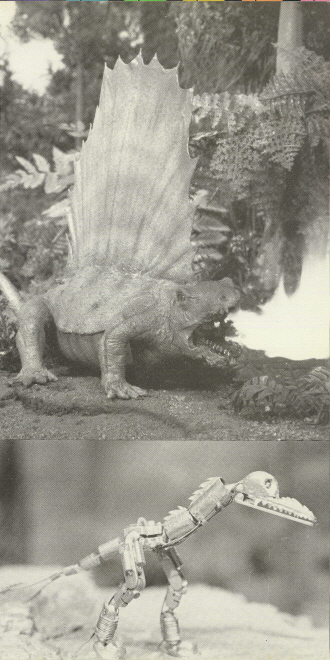

Cinefantastique (Vol. 6, No. 1, 1977): Behind the Scenes Visual Effects from Land of the Lost

Published January 13, 2016 Cinefantastique , Land of the Lost , Magazines/Zines , Sid and Marty Krofft , Special Effects/Visual Effects Leave a CommentRead the article at Pop Apostle, where I got the images. The visual effects for Land of the Lost were supervised by Gene Warren, who won an academy award for his special effects on George Pal’s The Time Machine (1960). Land of the Lost story editor David Gerrold, a Hugo and Nebula award-winner who wrote Star Trek‘s “The Trouble with Tribbles,” was not happy with the network’s meddling with the scripts, and resigned after the first season.

While Gerrold speaks highly of many who were involved with Land of the Lost, his disappointment with the show was multileveled. From his own point of view, the uncontrolled rewriting which took place after “approved” scripts had left his desk was intolerable. NBC’s Program Practices had a shot at them (his favorite story there involves a rifle which was changed to a cannon with the reasoning that children are less likely to imitate action performed with the latter). Also, the show’s directors were granted total rewrite power, as is often the case in film and television production.

In addition, the pressures of low budget production took a toll. The live action production schedule of two dates per episode allowed for little more than a reading of the lines. The end product, in Gerrold’s words, was “uncomfortable to watch– embarrassing– and we deserved the bad reviews we got everywhere…

Unfortunately, the dinosaurs began to die out with the science fiction in Land of the Lost. This is unfortunate because, in the beginning, the animation sequences often outclassed the live action (sound familiar?). Considering the time required for animation, and for tricky composite work, the very idea of doing both on a weekly series is ambitious to say the least. Nevertheless, that is what the Kroffts had in mind, and they engaged Gene Warren and Wah Chang, well known veterans of dimensional animation in feature films and commercials, for the job…

More Land of the Lost here.

Starlog #10 (December, 1976): Space Academy Article

Published January 13, 2016 Filmation , Magazines/Zines , Space Academy , Starlog 1 CommentEven though Space Academy didn’t air until September 1977, the idea was conceived in 1969 by Filmation’s Allen Ducovny, and development deals had been in the works with CBS since 1974. Originally, the idea was pitched to Gene Roddenberry as the basis for Star Trek: The Animated Series (1973-1974). According to Filmation chair Norm Prescott, Roddenberry rejected the idea, despite being offered a large sum of money. Filmation did end up producing the animated Star Trek—“the first attempt to do an adult show in animation,” Prescott gushed in 1973—with Roddenberry maintaining creative control.

When Space Academy premiered, everyone assumed it was chasing the success of Star Wars. It wasn’t, and Lou Scheimer was quick to quell the notion. The cadets in space acting as the “Peace Corps of the future,” as Scheimer described the show, was a descendant of Star Trek and Robert Heinlein’s novel Space Cadet (1948), as well as TV’s Tom Corbett, Space Cadet, on which Allen Ducovny had worked as a producer in the 1950s.

At the time, Space Academy had the biggest budget in Saturday morning history.