“The Lovecraftian Mythos in Dungeons & Dragons” is a fascinating and important supplement to Gods, Demi-Gods & Heroes (1976), which was itself a supplement to the original D&D set of 1974. The column was penned by two genre legends: Rob Kuntz, co-author of Gods, Demi-Gods & Heroes and the first edition Deities & Demigods (1980), and J. Eric Holmes, author of the first D&D Basic Set (1977). H.P. Lovecraft was, of course, listed as an “immediate influence” upon AD&D in Gygax’s famous Appendix N of the AD&D Dungeon Masters Guide (1979). Despite having little to do with the heroic fantasy genre as we know it, Lovecraft’s oeuvre is consistently identified with it, and has been just as influential on the development of fantasy role-playing as Tolkien and Robert E. Howard, Lovecraft’s long-distance friend.

There are a couple of reasons for this. First, the Cthulhu Mythos is fueled by occult lore and traditions: ancient magic, arcane knowledge and sacred mysteries, astral planes, psychic gateways, monsters of the deep, etc. As silly as the ’80s “satanic panic” was, the D&D universe (or multiverse) is alive with the same occult elements—employed as fictions, obviously, not facts. Second, Lovecraft, following Poe, used a journalistic approach when writing his weird fiction, sort of like a police procedural applied to supernatural phenomena. His world and its denizens are so convincing and internally consistent, in fact—so real—that actual cults have grown up around his writings and the anti-humanist, anti-rationalist philosophy they encompass. (See, for example, K.R. Bolton’s “The Influence of H.P. Lovecraft on Occultism.”)

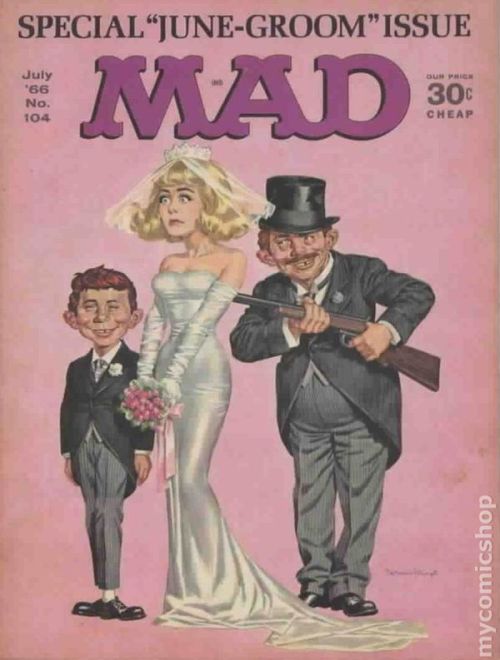

Like Tolkien, Lovecraft experienced a dramatic resurgence in the 1960s, when alternative spirituality and the quest for altered consciousness reached a new high (so to speak). The Moral Majority resented, among other things, the spiritual independence won by young people by the end of the Summer of Love decade, and they feared that D&D and other products of the imagination would corrupt—i.e. render freethinking—a new generation of youngsters. The difference between literate hippies and early geeks is that the former wanted to replace the “technocratic” real world with a new one based on love, freedom (in politics and consciousness), and a return to nature, whereas the latter simply wanted to create and play in a sandbox of alternative realities.

The idea of inserting Lovecraft into D&D sums up the glorious absurdity at the heart of fantasy role-playing: on the one hand, we want to escape to a fictional time and place that is less complicated than the real one, a world in which magic exists; on the other hand, we want our fantasy worlds to be systematically playable, and for that to happen, statistics must be applied to said worlds and the beings inhabiting them. It’s equal parts Romanticism and Enlightenment, art and science. Hence the brilliant entry for `Azathoth, Creator of the Universe’:

If Azathoth is destroyed the entire universe will collapse back to a point at the center of the cosmos with the incidental destruction of all life and intelligence.

Talk about game over. And the creator of the universe only has 300 hit points!

In The Dragon #14 (May, 1978), a letter from reader Gerald Guinn cheekily objected to a number of points made in the “Lovecraftian Mythos” article. J. Eric Holmes cheekily responded in The Dragon #16 (July, 1978). Both letters are below. Holmes’ response, along with the original article, are listed in Lovecraft scholar/biographer S.T. Joshi’s H.P. Lovecraft and Lovecraft Criticism: An Annotated Bibliography (1981).

A “Cthulhu Mythos” section (see tommorow’s post) expanded from the Dragon article appeared in the first edition of Deities & Demigods, but was famously removed from subsequent editions because TSR didn’t want to acknowledge its debt to Chaosium, which had acquired the rights—or the blessings of Arkham House, anyway, since Lovecraft’s works were and are in the public domain—for the Call of Cthulhu role-playing game.

For a comprehensive list of Cthulhu Mythos references in early D&D, see this post at Zenopus Archives.